|

I'll be on the February 22 episode of Launch Pad discussing Love in Any Language, airing on YouTube.

1 Comment

I was recently on the podcast Happiness Journey with Dr. Dan. Happiness Journey aims to tell uplifting stories amidst life's difficult struggles. Read more here.

Hey everyone! The latest Fault Zone anthology is out, and I contributed! Fault Zone is an award-winning anthology featuring the work of members of the San Francisco Peninsula branch of the California Writers Club. It comes out every two years and the latest version, which debuted December 1, is Fault Zone: Detachment. I contributed a story called "Parted, Not Separated."

You can get the anthology here on Amazon or wherever fine books are sold. Come listen to me talk about the world of Fremont-area writers on episode 98 of The Fremont Podcast, available on all major podcast platforms.

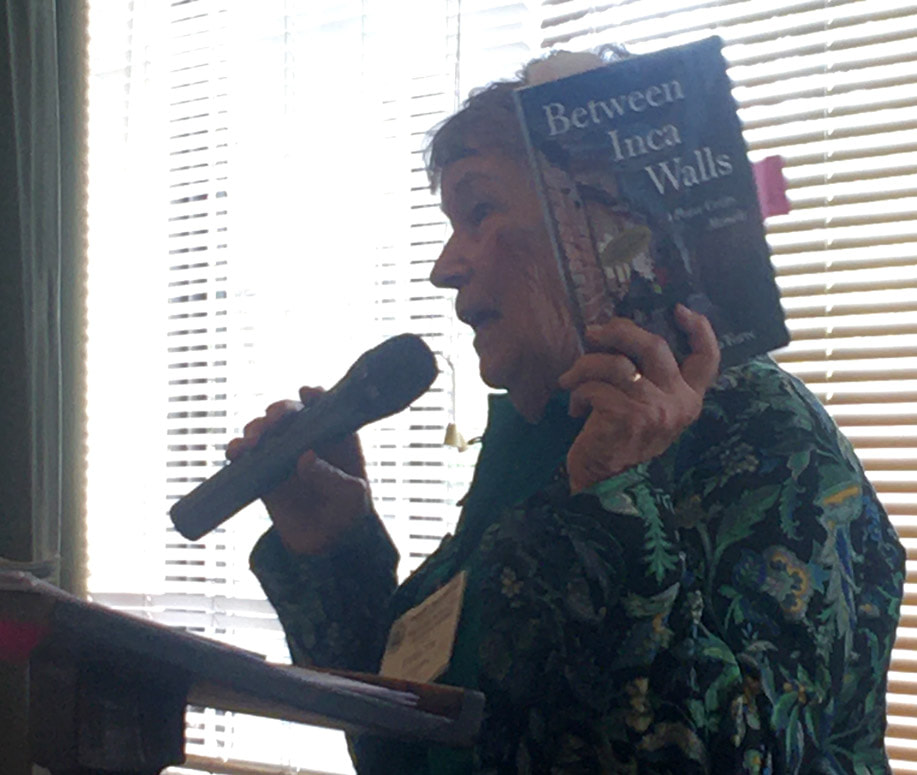

This is an adapted excerpt from my memoir, Between Inca Walls. At the Cusco railway station on November 22, 1964, my Peace Corps roommate Marie and I purchased tickets for the local train to Machu Picchu, not the more expensive train for tourists. Our plan was to see the ancient wonder of the world, then visit fellow volunteer, Larry at his site in Quillabamba.

Trains were one of the few things that arrived and left on time in Peru. We hopped aboard as soon as ours pulled into the station and settled onto a couple of scratched blue vinyl seats. After a short wait, we hear three toots of the whistle and began to move. The diesel engine labored forward, then backward, to pull, then push, the six passenger cars up the zigzagging rails on the side of the mountain and out of the city. Close to the top, burning oil replaced the musty smell of red clay soil. Smoke billowed outside the window of our car. I voiced concern to the man checking our tickets. “Just a dirty carburetor,” the man said. For the second year in a row, seven CWC members, including myself, were invited by former CWC-NorCal leader Carole Bumpus to attend the 35th National Kidney Foundation Authors Luncheon on October 28. Over 500 readers, writers, and booklovers met at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco to listen to four best-selling authors. Inspiring talks by those affected by kidney disease helped raise over half a million dollars for kidney transplants. Retired KQED radio host and author, Michael Krasny interviewed four best-selling authors about their writing processes, revealing many surprises.

My appearance on The Travel Addict podcast has just dropped. You can find it in the usual podcast places but here are a few:

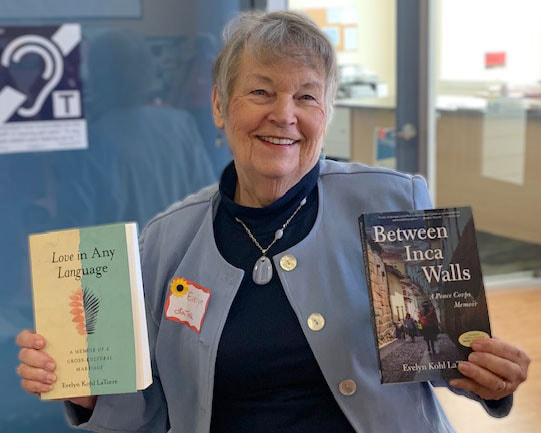

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-travel-addict/id1529802944 https://open.spotify.com/show/31sDaMn2zvtPOekza0y9OB https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9mZWVkcy5idXp6c3Byb3V0LmNvbS8xMjg4ODA4LnJzcw https://podcastaddict.com/podcast/3091275 https://www.stitcher.com/show/the-travel-addict https://www.podchaser.com/podcasts/the-travel-addict-1415058 I enjoyed speaking at the Fremont chapter of America Association of University Women at their installation luncheon. Thanks to all who purchased my memoirs. I sold out of both!

|

AuthorEvelyn LaTorre is a memoir writer living in Fremont, CA. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed